The Jewish War on White Australia

Part One

January 26 is Australia Day, a national public holiday marking the date the first permanent British settlers (mostly convicts) arrived in Sydney in 1788. These thousand or so souls — transported to the other side of the world and told to fend for themselves — laid the foundations for one of the most successful nations in history. Traditionally a day to celebrate this remarkable achievement, Australia Day has, in recent years, been attacked by leftwing activists who, emboldened by the escalating anti-White rhetoric of the intellectual establishment, have rebranded it “Invasion Day.” Every year sees shrill demands for Australia Day to be moved to another date, recast as a day of mourning, or abolished altogether. Despite the growing agitation against Australia Day, two-thirds of Australians favor retaining the date as a national public holiday.

Speaking to an “Invasion Day” protest rally in Melbourne this year, Aboriginal activist Tarneen Onus-Williams, screamed: “Fuck Australia,” expressing her hope “it burns to the ground.” A statement produced by her organization, the so-called Warriors of the Aboriginal Resistance (WAR), drew freely on the Cultural Marxist lexicon, insisting they “would not rest until this entire rotten settler colony called Australia, illegally and violently imposed on stolen Aboriginal land at the expense of the blood of countless thousands, burns to the fucking ground, until every corrupt and illegal institution of white supremacist, patriarchal, capitalist settler colonial power forced upon us is no more… Fuck your flag, your anthem and your precious national day. … Abolish Australia, not just Australia Day.” Aboriginal activist Tony Birch insisted Australia “does not deserve a national celebration in any capacity,” while Onus-Williams later claimed “people who celebrate Australia Day are celebrating the genocide of Aboriginal people, waving Australian flags in our faces. It’s disgusting.” Aboriginal activist Dan Sultan likewise maintained that Australia Day marks the “day that started the ongoing genocide of our people.” A local councilor for the city of Moreland (in Melbourne) claimed that commemorating Australia Day is “like celebrating the Nazi Holocaust.”

The origins of the “genocide” charge embedded in these comments can be traced (inevitably) to a coterie of Jewish academics and intellectuals including, most prominently, Latrobe University historian Tony Barta and Sydney University genocide studies professor and “anti-racism” crusader Colin Tatz. In collaboration with Winton Higgins, Anna Haebich, and A. Dirk Moses, these Jewish intellectual activists have succeeded in ensuring that “genocide is now in the vocabulary of Australian politics.” The word “genocide” was first used regarding Australia’s Aborigines by Barta at an academic conference in 1984 in a presentation entitled “After the Holocaust: Consciousness of Genocide in Australia” where he proclaimed that “genocide had indeed occurred here.”[A1] For Barta, a laudable focus on “the Holocaust” had “inhibited consciousness of the violent past that had enabled us to meet on ground named after the colonial secretary, Lord Sydney. The question was equally suppressed where I had settled with my family, the city named after Lord Melbourne.”[A2]

The policies of the British administrators of the Australian colonies of the late-eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and those of Australian state and federal governments in the twentieth century, cannot, by any objective standard, be regarded as “genocidal” as the term was defined by Raphael Lemkin, the Polish-Jewish jurist who coined it in 1944. The problem for anti-White activists has been that Lemkin’s definition, subsequently adopted by the UN, relies heavily on “intent to destroy,” which has proved problematic in an Australian context where, “without being able to prove intent on behalf of the colonial administration, the case for genocide is weak.”[A3] Barta, therefore, redefined “genocide” to make it encompass the totality of European colonial societies like Australia. His redefinition was “a way of obviating the centrality of state policy and premeditation” embedded in Lemkin’s ‘hegemonic intentionalist’ definition of genocide.”[A4]

Lemkin had defined “genocide” as involving “a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of the essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating groups themselves.” Aware no such plan or policies existed for Australia’s Aborigines, Barta — extrapolating the Marxian emphasis on economic relations for understanding sociological reality —argued for “relations of genocide” as an inherent feature of the interaction between Europeans and indigenous peoples in colonial societies like Australia. He writes:

Genocide, strictly, cannot be a crime of unintended consequences; we expect it to be acknowledged in consciousness. In real historical relationships, however, unintended consequences are legion, and it is from the consequences, as well as the often-muddled consciousness, that we have to deduce the real nature of the relationship. In Australia very few people are conscious of having any relationship at all with Aborigines. My thesis is that all white people in Australia do have such a relationship; that in the key relation, the appropriation of the land, it is fundamental to the history of the society in which they live; and that implicitly rather than explicitly, in ways which were inevitable rather than intentional, it is a relationship of genocide.

Such a relationship is systemic, fundamental to the type of society rather than to the type of state, and has historical ramifications extending far beyond any political regime. … My conception of a genocidal society — as distinct from a genocidal state — is one in which the whole bureaucratic apparatus might officially be directed to protect innocent people but in which a whole race is nevertheless subject to remorseless pressures of destruction inherent in the very nature of the society. It is in this sense that I would call Australia, during the whole 200 years of its existence, a genocidal society. [Emphasis added][A5]

Thus “all white people in Australia” are implicated in a “relationship of genocide” with Aborigines even if they (or their ancestors) lacked any such intention, had only benevolent interactions with Aborigines, or had no contact with them at all. When colonial, and later state and federal governments implemented policies designed to protect Aboriginal people, “genocide” was, for Barta, still “inherent in the very nature of the society.” This amounts to a sweeping moral indictment of all White Australians and their ancestors, and of Western civilization generally.

Barta’s redefinition of genocide enabled him to conclude that “Australia — not alone among the nations of the colonized world — is a nation founded on genocide.” He advocates this message “be the credo taught to every generation of schoolchildren—the key recognition of Australia as a nation founded on genocide.”[A6]

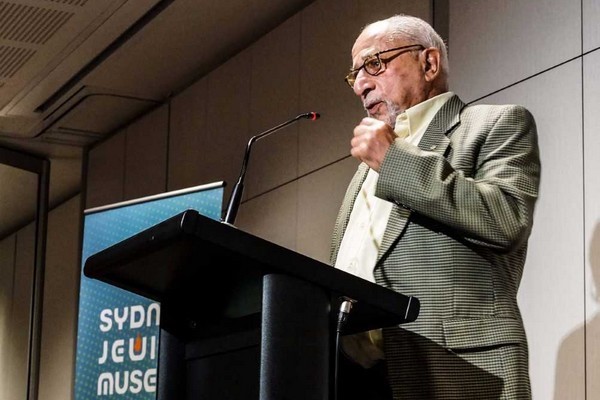

Decades of activism has succeeded in embedding this ahistorical notion in school curricula where White Australian children are encouraged to loathe not only their race, but also their ancestors and to disregard their achievements. The Sydney Jewish Museum is proudly playing its part in training Australian teachers “not only about the Holocaust” but also about “the Australian genocide.” It is this kind of anti-White activism, masquerading as objective historical analysis, that foments the seething hostility to White Australia seen in recent attacks on Australia Day.

This activism, and the widely-publicized removal of confederate monuments in the United States, prompted the disfiguring of a statue of Captain James Cook last year with the slogans “NO PRIDE IN GENOCIDE” and “CHANGE THE DATE” (see lead photograph). Lisa Murray, the City of Sydney’s official historian, defended this act of historical illiteracy (Cook had nothing to do with the First Fleet) for challenging the cultural power of White Australia. For her, the real vandals were the cleaners who removed the graffiti. “Should the graffiti have been removed?” she asked. “Is challenging the dominant historical narrative a legitimate part of the monument’s heritage? I ask again; should the graffiti have been removed. … Slave traders and representatives of colonial imperialism are equally on the nose in Britain, parts of Europe and America.”

Far from being a slave trader, Captain James Cook led a scientific voyage of discovery that charted the east coast of Australia for the first time in a ship containing botanists, an astronomer, artists and boxes of scientific equipment. This reality did not prevent Bronwyn Carlson, a Macquarie University associate professor who identifies as Aboriginal, from calling for tearing down not just Cook’s statue, but those of Lachlan Macquarie, Australia’s fifth colonial governor, on the basis that such statues “continue to represent those people who were part of genocide in this country.”

An “inspirational moment”

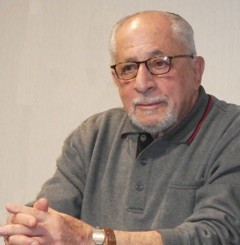

Recalling how he was inspired by Barta’s genocide thesis, Jewish academic Colin Tatz claimed it “set my wheels going about seeing not parallels or analogies but echoes of the Holocaust here — at the very least making me realize that genocide doesn’t have to be a sharp annihilatory episode confined to 1939 to 1945.”[A7] For Tatz, Barta’s presentation was an “inspirational moment and one that became central to my life thereafter.”[A8] Embracing and weaponizing the bogus notion of the “Stolen Generations” (discussed in Part 4), Tatz claims that as a result of “the public’s first knowledge of the wholesale removal of Aboriginal children, the dreaded ‘g’ word is firmly with us,” affirming that the “purpose of my university and public courses” is “to keep it here.”[A9]

According to Barta, Professor Tatz has “achieved his goals as an activist scholar.” His recent publications include: The Magnitude of Genocide, his memoir Human Rights and Human Wrongs, and his latest book, Australia’s Unthinkable Genocide. His work has, unsurprisingly, been praised to the skies by other Jewish activists and intellectuals. Israel Charny, Executive Director of the Institute on the Holocaust and Genocide in Jerusalem described The Magnitude of Genocide, as “an amazingly readable intellectual tour de force. Rarely have I seen the dread topic of genocide addressed so humanely and interestingly.” Acknowledging Tatz’s increasing success in conferring on Australia a global reputation for “genocide,” Barta contends that:

His attack on the membrane of ignorance and innocence was sustained and effective. Work on Australian genocide by other scholars combined with Indigenous activism began to bring international attention to bear on our history. I believe the most cited and defining intervention was Tatz’s 1999 paper “Genocide in Australia,” supported by his path-breaking work on racism. He succeeded in installing genocide studies as an academic discipline with institutional support and founding [the academic journal] Genocide Perspectives to stimulate Australian scholarship in an environment of ignorance, ideology and interests resistant to any association with genocide.[A10]

Barta and Tatz, in their determination to associate White Australians with “genocide,” obviously have agendas and interests of their own. Barta’s agenda leads him to insist that White Australians who reject his tendentious characterization of their history, “as settler-colonial, based on genocide,” will necessarily “deny others their history — as victims or perpetrators or bystanders — of conflicts elsewhere.”[A11]

The result of the “genocide denial” of White Australians is, he contends, the creation of “a climate in which Australia shows no compassion for those fleeing conflict and seeking better lives elsewhere.”[A12]

Here the real motivation of Barta’s intellectual activism is revealed: the inculcation of White guilt to suppress opposition to non-White immigration and multiculturalism. Barta’s colleague, A. Dirk Moses, recently associated critics of these policies with “Anders Breivik and Steven Bannon” for their suggesting “Western countries are succumbing to a poisonous cocktail of multiculturalism, Muslim immigration, political correctness and cultural Marxism that dilutes the white population and brainwashes young people at school and university.” According to Tatz, White people who reject his “genocide” label exhibit psychological disturbances manifested in “paroxysms, ranging from upset to extreme angst to even more extreme anger, when the (literal) spectres of genocide appear as facets of their proudly democratic histories.”[A13]

Inevitably, Barta and Tatz liken rejection of, or even ambivalence toward, their assertion that “Australia is a nation built on genocide” to “Holocaust denial.” Here they are joined by fellow Jewish academic and leading proponent of the “Stolen Generations” myth, Professor Robert Manne. Former editor in chief of The Australian, Chris Mitchell, noted Manne’s penchant for “manipulation of the idea of the Holocaust for political advantage, particularly in the Stolen Generations debate,” observing “this Holocaust tactic, like the related use of the word ‘denier,’ is a simple trick to undermine an opponent’s moral position when a polemicist has little intellectual case.”[A14] In levelling the “genocide” charge against White Australians, these Jewish activists seek to exert the kind of psychological leverage used so effectively against Germans, who, as Tatz notes, are “weighed down by the Schuldfrage (guilt question)” to such an extent that “guilt, remorse, shame permeate today’s Germany.”[A15]

Tatz has dedicated his professional life to ensuring that an analogous guilt permeates and becomes indissolubly linked with White Australian identity. In this endeavor, he is careful, however, not to detract from the metaphysical pre-eminence of “the Holocaust.”[A16] A writer for the Australian Jewish Newsnotes how “painful memories of the Holocaust still resonate and make us sensitive to comparisons,” emphasizing the supreme importance of ensuring that “recognizing the genocide of the Aboriginal inhabitants of Australia does not diminish the horror of the Holocaust.” To mitigate this danger, Tatz insists that, in discussing other putative genocides, scholars have an obligation to never “ignore, or evade, the lessons and legacies of the Holocaust in pursuit of other case histories.” The Holocaust must forever remain “the paradigm case, the one more analyzed, studied, dissected, filmed, dramatized than all other cases put together.” It must endure as “the yardstick by which we measure many things” and be the highest point on “a ‘Richter Scale’ that can help us to locate the intensity, immensity of a case so that we don’t equate all genocides.”[A17]

Jews at the forefront of Aboriginal activism

Australia’s Aborigines, in contrast to Jews, are a group characterized by extremely low average intelligence, and are, therefore, a poorly organized and essentially headless community devoid of effective leadership. It is unsurprising, therefore, that activist Jews, with their deep animosity toward Europeans, have been pivotal in establishing, funding, and leading Aboriginal activist organizations. This Jewish activist front is an adjunct of a broader campaign by transform Australia through non-White immigration and multiculturalism. Dan Goldberg, journalist for Haaretz and former editor of the Australian Jewish News, observed how “In addition to their activism on Aboriginal issues, Jews were instrumental in leading the crusade against the White Australia policy, a series of laws from 1901 to 1973 that restricted non-White immigration to Australia.”

Jewish journalist Debra Jobson insists that “Indigenous people need additional voices raised on their behalf given that the ‘tyranny of the majority’ can oppress within a democracy, as we can see in Trump’s America.” For the Jewish academic Nikki Marczak, the intellectual activism of Colin Tatz “embodies the relationship between the Jewish community and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.” Tatz, who describes himself as “the anthropologist of the White tribes of policy makers and bureaucrats,” is frustrated by “the reluctance of Aborigines to go international with their grievances. There is some external activity but not nearly enough when compared to the strategies of other minority groups.”[A18]

Noting the outsized Jewish contribution to Aboriginal activism in Australia going back decades, The Sydney Jewish Museum declared last year that:

When we say, “never again” to the Holocaust, we make a moral judgment about the German nation. We don’t accept the claim that they didn’t know. Many did know, and those who didn’t, should have. Thanks to the work of scholars like Colin Tatz and the work of lawyers like Ron Castan, in 1992 in the Mabo Case, the High Court was able to make a judicial statement that “Aborigines were dispossessed of their land parcel by parcel, to make way for the expanding colonial settlement.” … The late Ron Castan summarised it well when he commented on what motivated his legal work for Aboriginal people: “What was the meaning of my determination to do my part never to permit a future destruction of the Jewish people, if I just stood by and participated in the bounty and opportunity of the Australian nation?

In a 1998 speech, Castan implored the government to say it was sorry, citing Holocaust denial in his argument: “The refusal to apologize for dispossession, for massacres and for the theft of children is the Australian equivalent of the Holocaust deniers — those who say it never really happened.”

Tatz welcomes the fact that White Australian identity has increasingly broken down when “confronted with increasingly strident Aboriginal assertions and other ethnic challenges to the assimilationist mould. The old shibboleths about ‘one people’ people sharing the same hopes, loyalties, customs and beliefs began to fragment some time ago.”[A19] This social fragmentation is the direct (and fully intended) result of mass non-White immigration and multiculturalism: Jewish-originated and -championed policies designed to preserve Jewish particularism, while demographically, politically and culturally weakening a White Australia seen as threatening to Jews. The supposed benefits to Australian Jewry of this social transformation, most notably the diminished threat of the emergence of a mass movement of anti-Semitism among White Australians, is perceived to outweigh any negative effects of large scale immigration like the fact that “Some Australian Jews fear that migrants arriving from Muslim countries will contribute to anti-Semitic currents in Australia, inflame extremist groups and pose a threat to the relative peace they currently enjoy.”[A20]

Activist Jews know full well that racial and cultural heterogeneity are prime sources of national weakness. In a recent opinion piece entitled “Iran is Hardly a Nation and Will Likely Fall Apart,” Mordechai Kedar, a Zionist academic from Bar-Ilan University in Israel, contended that “there is no such thing as an Iranian people or an Iranian nation.” Instead, Iran is, he asserts, a country divided into various ethnic and religious groups riven by conflicting interests. He notes that “All these parts of the population have little in common, the awareness of nationhood is weak and, as a result, the state is always under threat of breaking apart.” He urges Western nations to facilitate this disintegration by finding “those anti-ayatollah forces” to “support them and empower them to bring Iran to the same end that met the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia by creating homogenous ethnic states on the ruins of the artificial state of Iran.” Divide and conquer remains the overriding Jewish group strategy pursued at both national and international levels.

Part Two

Colin Tatz is a stereotypical Jewish intellectual activist whose mindset is characterized by an intense ethnocentrism and an equally intense hostility to the traditional people and culture of the West. He reflexively subjects White people and Western societies to radical critique while exempting Jews from any equivalent evaluation. Identifying with, and taking great pride in the Jewish penchant for critiquing Western societies, Tatz claims that “Whatever else, I am a ‘product’ of Lasswell, of Cecil Roth and his notion that Jews (or some Jews) are the eternal protest-ants, of the doctrine of the Jewish Sages about tikkun olam. It is a synonym for social action, a conscious manipulating of skills to be proactive rather than reflective or contemplative.”[B1]

Cecil Roth, a Jewish historian, had argued “Jewish intellectualism” was primarily about “protesting at the insufficiency of the status quo.” Tatz agrees, and points to “a Jewish existential value which asserts that history has taught us that whatever is, no matter what it is, it is not good enough—hence the moral dictate of tikkun olam, that one is compelled to try to repair a flawed world.”[B2]

Of course, for “fiercely argumentative” Jews like Tatz, a “flawed world” is any world where Jewish interests are not forever prioritized. Tatz claims that “My activism is motivated by both personal and societal alienation,” and the “inner dynamic of my life, the foremost factor, is my version and interpretation of my Jewishness.” He notes that a “related if not conjoined propulsion” is “a lifelong devotion to matters of race and racism.”[B3]

Tatz makes no pretense of Jewishness being anything but an essentially biological phenomenon. Despite being an avowed atheist he remains a proud Jew, declaring his “unshakeable admiration, even a veneration for what I call Jewishness,” observing how “I remain within even while lacking faith, ritual, observance or any sense of Covenant.”[B4]

For Tatz, Jews comprise an easily identifiable ethnic type characterized by “body mannerisms, the shrugs, distains, the ever-present deprecatory and interrogative tenses of body and voice.”[B5]

Tatz is a descendent of the Litvaks, the Jews from Lithuania who, prior to their recent mass exodus from post-Apartheid South Africa to countries like Britain and Australia, made up ninety per cent of that country’s 120,000 Jews. According to Tatz, Lithuanian Jews were “economically forlorn and politically intimidated” and left Lithuania in “hordes” in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the majority landing in England, the United States and South Africa. He notes that “In South Africa I learned to live in a Lithuanian communitas, a transposed shtetl world of like-minded, like-speaking, like-behaving people. It was a society in transition from Tsarist oppression to a semi-welcomed ethnic minority moving into modernity.”[B6]

The hyper-ethnocentric mentality of South Africa’s Lithuanian Jews was encapsulated in “daily pontification about the Jewish-goyishe divide” and his grandfather’s refrain that “The worst of ours are better than the best of theirs.”[B7]

During World War II the South African government officially supported the Allies, with Prime Minister Jan Smuts appointed to Britain’s war cabinet. Despite this, most Afrikaners backed the Germans, and Tatz claims his childhood in South Africa in the 1940s was dominated by awareness of “a raging world war, civil strife between the pro- and anti-war forces, between English- and Afrikaans-speakers for political power, violent anti-Semitism in a country rife with fascist movements, the seeming calamity for Jews when the Nationalist Party came to power in the late 1940s, the fear of rising racial tensions of the 1940s, 1950s and beyond.”[B8]

Tatz claims to still be haunted by “domains that are oppressively black and cruelly white; and me, not quite a crowd—Jewish, alienated, migratory, and deeply troubled by food.”

Tatz’s obsession with the inveterate “anti-Semitism” of White people took deep root early in 1945 when, attending a cinema, “a loud but hidden voice hushed the cinema audience, urging children under twelve to leave the cinema for ten minutes or to place hands over their eyes. We stayed and peeked through fingers—at the first Bergen-Belsen footage. This was incomprehensible: how could people be so skeletal? Were they human? Were they us?” It was under the strength of such early influences that his “morbid obsession with genocide had begun.”[B9]

This ultimately led to his “studying, teaching, writing and talking a great deal about genocide and Holocaust especially.”[B10]

Tatz is one of those Jews, who, as he expresses it, bases “their quintessential beings—their political and psychological souls and psyches—on their genocidal victimhood.”[B11]

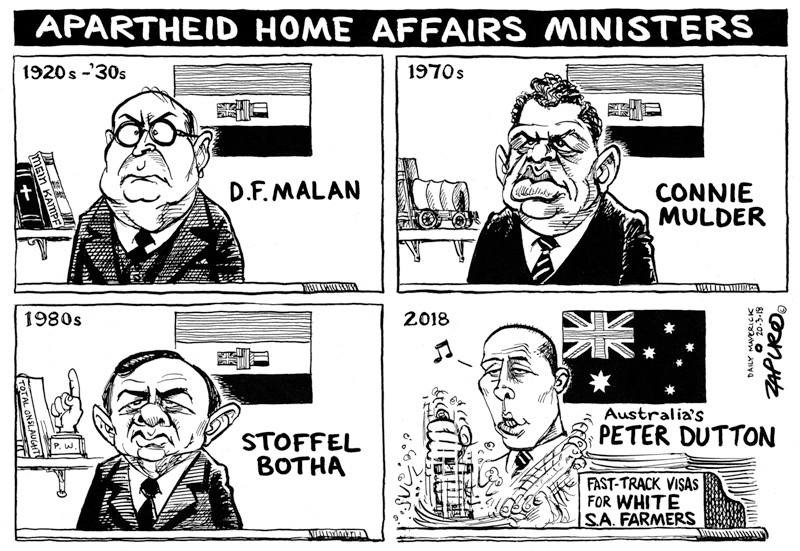

Hatred of Daniel Malan

In 1948 the Nationalist Party of Daniel François Malan came to power in South Africa on a platform of greater segregation of the four officially recognized races: Whites (or Europeans), the Cape Colored people (originally descendants of mixed unions between male Dutch East India Company officials, local farmers, soldiers, and settlers with local Hottentot and Bushman women), Indians (originally indentured Tamil laborers), and the Black majority (Bantu-speaking Africans known variously as Kaffirs, Natives, Bantu and Blacks). While Malan coined the term “apartheid,” South Africa’s first laws, regulations, and customs segregating the races date back to the 1770s. Apartheid was subsequently extended and entrenched under the “granite philosophy” of Dr Henrik Verwoerd in the 1950s who regarded it as model for the rest of the world to follow. Tatz claims that:

In early teenage years I began to take notice of the separate racial facilities: red buses and trams for Whites, green ones for Blacks, each with its own stops; separate ambulances; separate elevators in buildings; separate queues in post offices; different hospitals; all-White schools (we didn’t even know where Black children went to school); all-White cinemas, concerts; separate and much smaller stands for blacks at sports events; separate entrances and exits in buildings and businesses; Blanke and nie-Blanke signs on public benches and public toilets. Churches were segregated in the sense that Whites and Blacks attended in separate shifts: Blacks usually at the earliest possible time slots and Whites at the most convenient ones.[B12]

Tatz claims to have found all this deeply morally offensive, despite Jewish ethnic segregation having been a normative part of the Lithuanian Jewish subculture he claims to still revere. His real aversion to the South Africa of his youth lay, however, in what he describes as “the virulent anti-Semitism of Afrikaner nationalism and the right-wing movements.” According to Tatz, the atmosphere was such that “I didn’t really belong; on the surface, yes, but more a sense of toleration by virtue of being considered, but only barely, part of the ‘White race.’”[B13]

The South African state classified Litvaks, who made up 90 per cent of South Africa’s 120,000 Jews, as White, but neither the Afrikaners nor British descendants welcomed these clannish interlopers.

In the mid-1930s South Africa stopped all Jewish immigration. Malan, an Afrikaner nationalist acutely aware of the Jewish Question, declared in 1939 that “We have, moreover, the Jewish problem which hangs like a dark cloud over South Africa. Behind organized Jewry stands the organized Jewry of the world. They have so robbed the population of its heritage that the Afrikaner resides in the land of his fathers but no longer possesses it.”[B14]

According to Tatz, Malan, whom he regards as demonic figure, “cuddled and coddled” the various pro-German Shirt movements like the Ossewa Brandwag (Ox-Wagon Guard) who “attacked synagogues [and] Jewish shops . . . and printed and distributed Nazi leaflets and propaganda.” Malan, who would go on to lead South Africa as Prime Minister between 1948 and 1954, regarded Jews as an “unabsorbable minority.”[B15]

Despite their relative economic success, many South African Jews felt alienated by life under Malan’s rule, and Tatz claims that “Here, indeed, was a special kind of alienation, of belonging but not quite belonging, of Jews hoping, believing, even preaching, that they were mainstream South Africans but somehow sensing that they had no place in this white South Africanism.”[B16] Tatz heard that thirteen Jewish families had migrated to Australia in 1948 “on the basis that life under the frightening Dr Malan wasn’t livable.”[B17] He was, a decade later, to join them.

As a deeply (and stereotypically) alienated Jew, Tatz assessed that life in apartheid South Africa presented him with five options. He dismissed the first, of identifying with mainstream Afrikaner nationalism, as “impossible.” The second, of identifying with Black nationalist movements, initially attractive, was ultimately not to his taste either. The third option, embraced by many South African Jews, was to join the Communist Party. Tatz claims he rejected this option because he didn’t need the “false camaraderie which accompanied Jews when they joined the Russian Revolution in 1917.”[B18] The fourth option was “to put on blinkers and pretend that there was nothing amiss around me.” For the intensely political Tatz, this was simply “out of the question.” The fifth option, which he initially adopted, was to stay in South Africa and “write critiques of the system.” He pursued this option while a postgraduate student at the University of Natal, and it led to his first book, Shadow and Substance, written as a moral critique of South Africa’s racial policies. The sixth option, which he ultimately embraced, was “to remove myself from this environment altogether.”

The disingenuous nature of Tatz’s moral opposition to apartheid South Africa is revealed by the fact that, having committed himself to emigration, his first preference was to head to Israel: a nation founded on terrorism, ethnic cleansing, and institutionalized ethnic discrimination and apartheid. Tatz recounts that by 1959 he had decided to leave South Africa with his wife Sandra by the end of 1960. His plans changed when he was informed that an academic job was unlikely to become available in Israel because rich American professors “were free to volunteer their vacation services and they occupied all positions.” Tatz claims that, “Pretty shaken at the rejection of what I believed was young and willing talent, we were at a loss. Part of me still tells me that we should have persisted, and that Israel was the emotionally sensible place to be.”[B19]

Tatz sees no irony in his desire to leave a supposedly morally-objectionable South Africa for the Jewish ethno-state of Israel.[B20] One searches in vain through his voluminous writings on “genocide” and “racism” for even passing acknowledgement that Israel was founded on ethnic cleansing (where ninety per cent of the Indigenous Palestinian population have been killed or expelled). The Zionist project has created some eight million Palestinian refugees, and the highly abusive, violent and indefinite confinement of presently five million Palestinians: two million in the Gaza Strip and three million in the West Bank. Israeli Palestinians live as third-class citizens under a two-tier political and legal system. None of this is ever mentioned, let alone condemned, by the sanctimonious Tatz, nor the fact that Israel’s immigration policy openly discriminates against non-Jews, and bans marriage between Jews and non-Jews.

Instead he remains a fervent Zionist, and recounts how arriving in Israel in 1976, thanks to a state-sponsored three-week visit, “was an emotional turmoil evoking pangs about why I wasn’t there as a resident.”[B21] While in Israel, Tatz was given access to figures like General Moshe Dayan, Prime Minister Yitzak Rabin, the Eichmann Prosecutor Gideon Hausner and Foreign Minister Abba Eban. He recalls that “I hardly needed such a visit to make me Israel-aware, but the visit evoked an emotional reaction. I couldn’t wait to go there again and again.”[B22]

The rank (but entirely characteristic) hypocrisy of this Jewish intellectual activist is also evident in his having written several books about the “racism” supposedly endemic in Australian sport while participating in the Maccabi Games in Israel—a strictly Jews-only sporting festival. In his 2011 book One-Eyed: A View of Australian Sport, he contended that Australia’s traditional preoccupation with sport was evidence of the deep-seated racism and misogyny that undergirded White Australian society, and touted his book is a “strong and provocative piece of social and political criticism” that explores themes of “militarism, or Empire-ism, Britain’s motherhood, sport and war, sport as moral education, anti-femininity, racism” amongst others.[B23]

Since the end of apartheid, over 15,000 South African Jews have migrated to this incurably “racist” Australia. Tatz claims these Jews “are the world’s most educated émigrés, 70.8 per cent at tertiary level, the most well-heeled, the most cosmopolitan in the way they travel, the only migrant group capable of spending time and money coming on visits before selecting their relocation spots.”[B24]

Even he has been taken aback by the insularity of these newcomers, observing how “socially, spatially, culturally, religiously, they huddle in enclaves of their own creation.” “Marrying out” for these intensely parochial Jews means marrying a non-South African Jewish spouse.

Tatz ascribes this hyper-ethnocentrism to the fact that “the shtetl remains engraved in their immigrant souls.” From the time of the mass Jewish exodus from Lithuania to South Africa in the early twentieth century, these Jews were, he notes, “saturated” with the notion of separateness. Ever-willing to wallow in the soothing psychological balm of lachrymose Jewish victimhood narratives, he also attributes their extreme ingroup preference to “the specter of antisemitism, the dark shadow of rejection by an anti-Semitic and intolerant world.” It is only among themselves, he maintains, that they can “relax at least for a while—laugh, cry, be brash, busy, creative, funny and not worry about what the goyim think.”[B25]

The reputation of South African Jews in Australia took a significant hit in 2009 when the Sydney Morning Herald reported that Barry Tannenbaum, a South African Jewish immigrant, had scammed investors out of $1.5 billion in a Ponzi scheme that was likened to Bernie Madoff’s crime in the United States.

Tatz evinces no embarrassment at the state of the post-Apartheid South Africa that he and countless other Jews strived to bring about (Jews made up all six of the “whites” indicted in the Rivonia Trial of 1963 when several leaders of ANC, including Mandela, were given life sentences for plotting terrorism against the government). “I have taught many courses on South African racial history” he observes, “and still find the energy to read of events in the ‘rainbow country’—even with a doom-laden sense of watching a failed state or one looking perilously like one.”[B26]

Ignoring the ongoing mass murder of White South African farmers, he notes with anguish how Cape Coloreds, now ten percent of the population, “are increasingly converts to militant Islam, filled with Jihadist hate and violence, especially towards Cape Town’s remnant Jewish population.”[B27]

Arriving in Australia

Having been generously allowed to migrate to Australia in 1960 to pursue postgraduate studies at the Australian National University in Canberra, Tatz repaid the hospitality of his new host by plunging into what he describes as the “unexpectedly depressing realm of Australia’s race relations.”[B28]

Arriving in Canberra he quickly plugged into Jewish ethnic networks.

On my first day I walked to the nearest payphone, looked up J for Jewish, found a number and spoke to a public servant, David Smith, later official secretary to five Governors-General and knighted. Stay where you are, he said, and 20 minutes later we were under his family’s friendly wing. The very small Jewish community met for a few services at the Riverside Huts and for the high holy days in a hired trade union hall, and although we couldn’t contribute financially we were accepted as fully-fledged members of that small society[B29]

Tatz speaks with contempt of the Anglo-Australian society of the 1960s and 1970s that he and his family “endured.” A move from Canberra to Melbourne was prompted by his appointment as a lecturer in politics and sociology at Monash University. Life in a prosperous, safe and orderly White middleclass suburb of Melbourne was purgatory for Tatz, who recalls how “We lived in Mount Waverley—then a social and cultural disaster zone but reasonably close to Monash—and endured that suburban wasteland from 1964 to the end of 1970. The American Jewish comic Allan Sherman once said he lived in 10 Sparrowfart Lane; our house was definitely number 8.”[B30]

Further ethnic networking led to his wife landing “a useful and attractive job at Jewish Welfare in [the suburb of] South Yarra, as assistant to Walter Lippmann, an outstanding figure in Jewish multicultural and migration affairs.”[B31]

Walter Lippmann was, as I have previously discussed, the driving force behind getting “multiculturalism” embedded at the heart of state and federal government social policy. Lippmann also successfully lobbied for the creation of Australia’s first dedicated refugee policy and, then, its expansion in numbers and countries of origin.

Distaining to send his three children to a local school “heavily populated by a Christian Science congregation,” Tatz approached

Bialik College, a Zionist-oriented Jewish Day School in [the inner Melbourne suburb of] Hawthorn. Despite our inability to meet the fees, the Israeli principal wanted the three children. It was arranged that we could make desultory payments until our fortunes improved. The school was good for the children. They rode to school in a taxi subsidized by Bialik but even with that trip taken care of, Sandra drove something like 80km daily.[B32]

Tatz’s willingness to go to extreme lengths to avoid sending his children to a local goyish school is noteworthy given his claims to have first become aware of “social injustice,” and that “something was particularly amiss for Jews” in South Africa, in noticing the separation of Jewish and non-Jewish students at his school in South Africa, the King Edward VII High School, where “We were kept truly apart . . . with no explanation or justification.” For Tatz, this “embryonic awareness launched a lifelong journey into the study of politics and race.”

Tatz left Monash University in 1971 after being appointed the chair of politics at the University of New England in New South Wales where he established courses “on comparative race politics, racism and nationalism, and on Aboriginal studies for teacher trainees in particular.”[B33] In 1982 he took up the chair of politics at Macquarie University in Sydney. After studying at the Yad Vashem Holocaust Center in Jerusalem in 1986, he founded the Centre for Comparative Genocide Studies and introduced a genocide studies course at Macquarie. It was during repeated visits to Yad Vashem in the 1980s that he claims his “experiences, observations and analyses of racism merged into a stream of Holocaust consciousness.”[B34] Yad Vashem provided him with a new “analytical toolbox” in which the Holocaust connected seemingly disparate cases of racism, such as those experienced by Aboriginal Australians and Native Americans, that at first glance “have little in common with processes in the Third Reich.”[B35] Dissatisfied with funding, Tatz relocated the center to the University of New South Wales in 1999.

Kevin MacDonald has written extensively about the Jewish guru phenomenon, of Jewish intellectual leaders who take on a semi-divine status in the minds of their adoring acolytes. Tatz’s guru is the “great Holocaust scholar” Yehuda Bauer who he describes as his “mentor and inspiration.”[B36] Tatz first met his idol at Yad Vashem during the first Gulf War in 1991, and claims hearing or reading Bauer always left him awestruck by his “intensity, passion, and dedication to both detail and to the broader sweeps of that history.”[B37]

The lessons that Tatz internalized from his guru are that White people are inveterate and incorrigible “anti-Semites” and that the hopes of Jewish activist organizations of eventually eliminating “anti-Semitism” are illusory:

Yehuda Bauer once said that of the death of 50 million people worldwide because of Hitler’s war against the Jews doesn’t deter people from hating, baiting and harming Jews, then nothing will. A sobering thought as I have come to accept his dictum that anti-Semitism is part of the Western world’s intellectual and populist baggage. It has always been there and always will be despite some valiant efforts by Jewish organizations to combat it. … If one believes that anti-Semitism is a “disease,” a “mental disorder,” one can understand the efforts at therapy. If one accepts it as “normal,” one can stop chasing down badly or insultingly worded crossword clues, offbeat comments on talkback radio, criticism of Israel and its military and [golf club] Royal Sydney’s membership policy. I believe that sanction is the only plausible remedy, one that can halt overt action against people and property; some Australian jurisdictions are halfway there with the criminalization of hate speech and incitement to racial hatred. Although you can do something to stop anti-Semitic behavior, you can’t stop the mindsets.[B38]

A proponent of the full criminalization of “anti-Semitism,” Tatz is generally skeptical of attempts by Jewish activist organizations to fight criticism of Jews through re-education programs like “Click against Hate,” an “early intervention” program run by Australia’s Anti-Defamation Commission for schoolchildren from Years 5 to 10 that is funded by billionaire Jewish property developer (and ardent Zionist) John Gandel. Tatz maintains that:

Race relations education programs the world over have shown that trying to educate people out of their racism doesn’t work. Founded in 1913, the reputable Anti-Defamation League (ADL) in the United States is dedicated to fighting anti-Semitism and all forms of bigotry. It has had a few wins and a few interventions, but essentially one has to say that its campaigns on anti-Jewish sentiment and behavior has had little, if any, success in broad terms. (Much of the anti-defamation activity the world over treats racism as some form of illness and in need of a therapeutic approach. For reasons difficult to comprehend, making racism illegal is rarely considered an option.)[B39]

Despite his skepticism regarding the effectiveness of Jewish re-education programs, Tatz remains a staunch advocate for the introduction of courses about Aborigines, anti-Semitism, and “the Holocaust” in schools and universities. Despite the ubiquity of “the Holocaust” in Western culture, with its constant solicitations to White guilt, Tatz finds “disturbing” the “reluctance of curriculum-setting people, in schools and universities, to take the subject on board.”[B40] In 2012 the New South Wales Jewish Board of Deputies succeeded, after intense lobbying, in having study of “the Holocaust” mandated for all New South Wales school students. Tatz recommends that all students should make a pilgrimage to the Holocaust shrine of Auschwitz. His massage is “to go and see it, feel it, cry, gasp, take very deep breaths, and then recognize, in this very place, the stark reality that Jews will never be liked, let alone loved; that despite European Jewry enriching the world, much of the European world wanted to be rid of Jews and assisted the Nazis in their mission.”[B41]

Part Three

Critiquing Australia

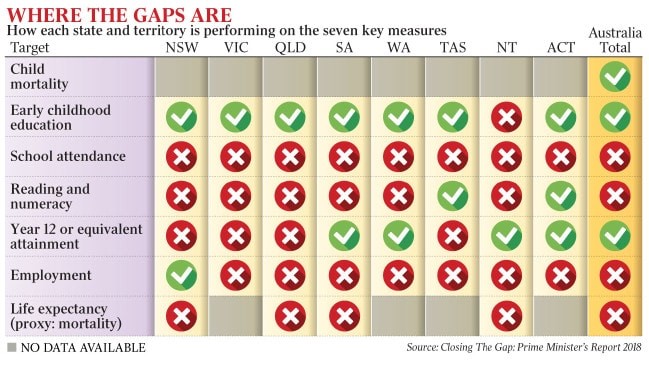

From his arrival in Australia in 1961, Colin Tatz quickly identified those aspects of Australian society to his extreme distaste—what he describes as the “warts, some of which I have watched grow into malignant lumps.”[C1] Foremost among these, he claims, was the gap in social indicators between White Australians and the Aborigines. Australia’s indigenous population has always had the worst health, and the lowest educational, occupational, economic, and social status of any identifiable section of the Australian population. The annual report on progress in the Australian government’s strategy of “Closing the Gap” between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians has been called an “annual statement of failure, a catalogue of defeat.”

In 2015–16, $33.4 billion of Australian taxpayers’ money was spent on Aboriginal programs: $44,886 for every Aborigine in the nation. More than a thousand government initiatives seek to ameliorate the myriad manifestations of Aboriginal social and economic dysfunction. In many communities there is one service for every five residents. Wilcannia, in New South Wales, for example, had 102 funded services in 2012 for an indigenous population of 474. Despite this, Aboriginal people continue to trail other Australians in virtually all metrics including life expectancy, child mortality, health, education and employment. As journalist Grace Collier noted: “The problems are shocking but seem intractable—we feel horrified and helpless; we don’t know how to assist. Worse, no matter how much money we give, it is never enough. Thirty-three billion dollars a year goes off into the ether, never to be seen again, and nothing seems to ever improve.”

Despite the burgeoning funding of proliferating Aboriginal programs, the Aboriginal leader and activist June Oscar had the nerve to excoriate successive governments for “abandoning” their commitment to tackling Aboriginal disadvantage, and for failing to execute and adequately fund Closing the Gap. Rather than responsibility for the lack of any improvement residing with Aboriginal people themselves, Oscar maintained that failure of achieve the Closing the Gap targets measured nothing but “the collective failure of Australian governments to work together and stay the course.”

Colin Tatz is dismissive of government efforts to close the gulf between Aborigines and non-Aborigines, arguing this approach “reduces Aboriginal Australians to a range of indicators of deficit, to be monitored and rectified towards government-set standards.”[C2] In his view, the Closing the Gap strategy is more about “achieving government desires to alter statistics that look bad for us, a First World prosperous country.”[C3]

Tatz attributes the dysfunction in Aboriginal communities not to Aborigines themselves, but to the poor treatment he claims they receive at the hands of White Australian bureaucrats, whose efforts to relieve Aboriginal distress are merely designed “to make the ‘rescuers’ look better, more like decent and democratic colonisers.”[C4]

This attempt to blame the intractable social pathologies of Australia’s Aborigines on the evil legacy of European colonialism, “genocide” and “racism” is the purest anti-White propaganda. The traditional hunter-gatherer lifestyle of the Australia’s Aborigines was severely disrupted by the arrival of Europeans. There were around 300,000 Aborigines in Australia at the time of European colonization in 1788. Their numbers declined considerably in the decades that followed, mainly due to diseases contracted from Europeans for which they had no immunity. Aborigines were also killed by Whites in violent clashes on the frontier—often in reprisal for attacks on Whites. Violence against Aborigines was specifically prohibited by the governing authorities, and White settlers were charged with murder and executed for killing Aborigines. The 1961 census reported that the Aboriginal population of Australia at around 106,000. This had increased to 171,000 by 1981, and, incredibly, to over 800,000 in the 2016 census, suggesting the $33 billion in Closing the Gap programs is fueling a population boom. This figure has been inflated by those with tiny amounts of Aboriginal ancestry (or none) now claiming to be Aboriginal to take advantage of the ever-multiplying indigenous welfare programs, scholarships and career opportunities.

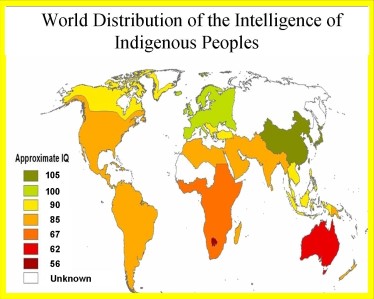

Denial of low Aboriginal IQ

Notwithstanding the fact European colonization had a range of negative effects on Australia’s Aborigines, the real (though never acknowledged) source of their dysfunctional communities is their extraordinarily low average intelligence. According to psychologist Richard Lynn, the first attempt to estimate the intelligence of the Australian Aborigines was made by Francis Galton in 1869. From descriptions of their accomplishments, he estimated that their intelligence was approximately three “grades” below that of the English. Lynn explains that: “In Galton’s metric, a grade was equivalent to 10.4 IQ points. Hence in terms of the IQ scale, he estimated the Australian Aborigine IQ at 68.8. Seventeen studies of the intelligence of Australian Aborigines assessed by intelligence tests have shown that this was a fairly accurate assessment. … The median IQ of the seventeen studies is 62 and represents the best estimate of the average intelligence of Australia’s Aborigines”[C5]

The findings from studies into Aboriginal IQ have been corroborated by a study showing Aborigines have slower reaction times (reaction time being moderately correlated with IQ). Four studies of the average IQ of Aboriginal-European hybrids put it at 78—midway between the IQs of Aborigines and Europeans. The low average intelligence of Aborigines is supported by their very low levels of educational attainment. Lynn notes that: “Aborigines do poorly in education, consistently with their low intelligence, showing that their low cognitive abilities are not confined to their performance on intelligence tests.”[C6]

A recent report from the Grattan Institute found that remote indigenous children are five years behind the typical student in numeracy, six years behind in reading, and seven to eight years behind in writing by the time they are in Year 9 [aged 15]. “In other words,” according to the study author Peter Goss, “the average Year 9 indigenous student in a very remote area scores worse on the NAPLAN writing test than the average Year 3 [aged 8] non-indigenous student.” The reality is that a population with a mean IQ of 62 (or even 78 for mixed race Aborigines) is incapable of functioning effectively in a modern technological society like Australia.

Tatz exposes himself as an intellectual charlatan in his comprehensive rejection of the accumulated evidence demonstrating racial differences in average intelligence. In his determination to subordinate the truth to his ethnic agenda, Tatz, who purports to be “meticulous about matters of fact,” dismisses the accumulated psychometric evidence by deploying the epithet “scientistic racism.” His rhetorical technique is not to cite contradictory evidence (for there is none), but to catalogue the supposedly wrongheaded and malevolent claims about race that, he insists, Western scientists have historically used to justify the oppression of non-Whites:

Appreciating the race factor also requires going through the growth of “scientistic racism,” that is, the works of anatomists and physical anthropologists who began to examine and compare the human form and then started to attribute social characteristics to the physical ones. When physical forms as such could not establish a “suitable” hierarchy of races, they turned to measurements of “intelligence,” using craniology (skull measurement) as the ultimate criterion. Researchers concluded that Caucasians—named after what was thought to be the perfect (“white”) skull found in the Caucasus mountains in Russia—had the largest brain casing (87 cubic inches), according to physician Samuel Morton in his Crania Americana (1839). Native Americans had a mean volume of 82 cubic inches (measured using mustard seed) that, Morton deduced, made them slow of thought, averse to agriculture, vengeful, and lovers of warfare. Ethiopian and black skulls held an even smaller quantity of seed (78 cubic inches) but their owners’ bodies were the more muscular. Thus, laboratories spawned the brain versus brawn (or white versus black) dichotomy that is still prevalent in many circles. Australia’s Indigenous people (“Australoids”) had less skull volume than any other people, and were ascribed as having even more reduced capacities—a furphy propagated in Australian school texts until the 1980s.[C7]

Tatz cites no actual evidence to contradict this “furphy,” and conveniently ignores more recent and precise measures of skull volume including seven studies showing the average brain size of Aborigines is significantly smaller that Europeans (brain size being correlated with IQ at approximately 0.4). The most authoritative study of Aboriginal brain size is that of Smith and Beals (1990) which gave a brain size difference of 144cc. or about 10 per cent. Tatz also completely rejects the validity of IQ testing, including the Stanford-Binet intelligence test which he claims is “still in use, or misuse, today for streaming children into different levels of education, for separating classes of people, the bright from the simple, and so on.” He contends that, “No matter what spin one puts on modern IQ testing, it remains of the same genre and ‘scientific’ validity as skull measuring.”[C8]

For Tatz, IQ tests were developed as part of the conspiracy by White supremacists in the U.S. to create a society that was White and Protestant and excluded Jews and Blacks.[C9]

Such sophistry emanates from a man extolled by a colleague for his “fierce fidelity to truth,” a trait that has “won him a well-deserved international reputation as an intellectual,” and has “attracted the toxic enmity of those who have a vested interest in untruth.”[C10] Tatz aptly characterizes his own egregious denial of racial differences in intelligence in noting that “individuals and collectives usually know (or can reasonably infer) a great deal more than they’re prepared to acknowledge. Denialist discourses present accounts of circumstances in question that obliterate or falsify their actual character. … The common technique is quintessentially assertion and contention rather than any attempt at demonstration or affirmation of their viewpoints.[C11] He shares this trait with fellow Jewish academic and “Stolen Generations” propagandist, Robert Manne, who, as historian Bain Attwood has pointed out, “asserts rather than argues.”[C12]

Dismissing over a century of psychometric evidence showing a gulf in mean IQ between White Australians and Aborigines allows Tatz to ascribe the dismal state of Aboriginal communities exclusively to White malevolence. He even makes the laughable claim that, prior to the 1960s, “Aborigines were, in general, the most law-abiding sector of the Australian population,” whereas now they would have to be “considered, statistically, to be the most criminal population on the planet.”[C13]Indeed, he claims, “as more education, training and intervention programs are established, so more and more youth are imprisoned. Some 28 percent of all prisoners in custody are Aboriginal, a figure that brands them as the world’s foremost criminals.”[C14] The link between low intelligence and a greater propensity for violent crime has been well established by criminological research.

A study recently published in the British Medical Journal by Australian researchers found, in a study of about 100 young people aged 10–17 incarcerated in Western Australia (which has a very high Aboriginal prison population), 89 per cent had at least one area of severe neurodevelopmental impairment, such as problems with memory, cognition or motors skills. The study found about a quarter were found to have to have an intellectual disability, with an IQ score at or below 70. The director of the study, Carol Bower, noted that “Almost half the young people had severe problems with language, how to listen and reply and explain what they think.”

Denial of the anthropological record

In his risible claim that Aborigines were once “the most law-abiding sector of the Australian population,” Tatz disregards anthropological evidence showing Aboriginal societies were, prior to contact with Europeans, extremely abusive to women and children and generally violent. In 1995 paleopathologist Stephen Webb published his analysis of 4500 individuals’ bones from mainland Australia going back 50,000 years. These bone collections were at the time being handed over to Aboriginal communities for re-burial, which stopped any follow-up studies.

He found highly disproportionate rates of injuries and fractures to women’s skulls, with the injuries suggesting deliberate attack and often attacks from behind, perhaps from domestic squabbles. In the tropics, for example, female head injury frequency was about 20–33%, versus 6.5–26% for males. The most extreme results were on the south coast, from Swanport and Adelaide, with female cranial trauma rates as high as 40–44%—two to four times the rate of male cranial trauma. In desert and south coast areas, 5–6% of female skulls had three separate head injuries, and 11–12% had two injuries.

The high rate of injuries to female heads was very different from the results from studies of other peoples. His findings, according to anthropologist Peter Sutton, confirm that serious armed assaults were common in Australia over thousands of years prior to the arrival of Europeans.

From British settlement in 1788, Europeans arriving in Australia were shocked at the extreme physical violence Aboriginal men inflicted on their women. Watkin Tench, a British marine officer who arrived on the First Fleet, noticed a young woman’s head “covered by contusions, and mangled by scars.” She had a spear wound above her left knee caused by a man who dragged her home to rape her. Tench wrote: “They are in all respects treated with savage barbarity; condemned not only to carry the children, but all other burthens. They meet in return for submission only with blows, kicks and every other mark of brutality.”[C15] Tench observed that when an Aboriginal man “is provoked by a woman, he either spears her, or knocks her down on the spot; on this occasion he always strikes on the head, using indiscriminately a hatchet, a club, or any other weapon, which may chance to be in his hand.” British soldier William Collins recounted how “We have seen some of these unfortunate beings with more scars upon their shorn heads, cut in every direction, than could be well distinguished or counted.”[C16]

In 1802 an explorer in the Blue Mountains in New South Wales wrote how, for a trivial reason, an Aboriginal “took his club and struck his wife’s head such a blow that she fell to the ground unconscious. After dinner … he got infuriated and again struck his wife on the head with his club, and left her on the ground nearly dying.”[C17] In 1825, the French explorer Louis-Antoine de Bougainville observed that “that young girls are brutally kidnapped from their families, violently dragged to isolated spots and are ravished after being subjected to a good deal of cruelty.”[C18]

George Robinson observed in the 1830s that Aboriginal men in Tasmania “courted” their women by stabbing them with sharp sticks and cutting them with knives prior to rape.[C19] A contemporaneous account by an ex-convict named Lingard noted that: “I scarcely ever saw a married woman, but she had got six or seven cuts in her head, given by her husband with a tomahawk, several inches in length and very deep.”[C20]

Explorer Edward John Eyre similarly observed that “women are often sadly ill-treated by their husbands and friends. … They are frequently beaten about the head, with waddies [clubs], in the most dreadful manner, or speared in the limbs for the most trivial offences. … Few women will be found, upon examination, to be free from frightful scars upon their head, or the marks of spear wounds about the body. I have seen a young woman, who, from the number of these marks, appeared to have been riddled with spear wounds.”[C21]

Tribal warfare and paybacks were endemic among Aborigines. The anthropologist T.G.H. Strehlow witnessed a battle in 1875 in Central Australia which was triggered by a perceived sacrilege: “The warriors turned their murderous attention to the women and older children and either clubbed or speared them to death. Finally, according to the grim custom of warriors and avengers they broke the limbs of the infants, leaving them to die ‘natural deaths.’” The final number of the dead could well have reached the high figure of 80 to 100 men, women and children. Subsequent revenge killings by the victims’ clan amounted to more than 60 people.[C22]

Respected historian Geoffrey Blainey estimated that annual death rates among Aboriginal tribes in the Port Phillip Bay area were comparable with countries involved in the two world wars. A tribe in Arnhem Land in Northern Australia was so violent in the 1920s it could be placed among the world’s most lethal societies, with a homicide rate of at least 300 per 100,000 (which Stephanie Jarrett, in her book Liberating Aboriginal People from Violence, suggests could be grossly under-estimated). This is over three times that of the country with the highest homicide rate in the world in 2017 (El Salvador at 82.84 homicides per 100,000), and almost three times that of the city with the highest homicide rate in the world in 2017 (Los Cabos in Mexico at 111.33 homicides per 100,000).

Escaped convict William Buckley, who lived for over three decades with an Aboriginal tribe around Port Phillip Bay in present-day Victoria in the early nineteenth century, witnessed constant raids, ambushes and massacres. Buckley noted how the Watouronga tribe of Geelong in night raids “destroyed without mercy men, women and children.”

Buckley also described the practice of cannibalism between the warring tribes of the area, including the practice of eating flesh from the legs of slain warriors which “was greedily devoured by these savages.” He mentions their practice of mortuary cannibalism for love, relating that “they eat also the flesh of their own children to whom they have been much attached should they die a natural death,” and described how:

They have a brutal aversion to children who happen to be deformed at their birth. I saw the brains of one dashed out at a blow, and a boy belonging to the same woman made to eat the mangled remains. The act of cannibalism was accounted for in this way. The woman at particular seasons of the moon, was out of her senses; the moon—as they thought—having affected the child also; and certainly it had a very singular appearance. This caused the husband to deny his being the father, and the reason given for making the boy eat the child was, that some evil would befall him of he had not done so.[C23]

Tatz ignores Buckley’s detailed eyewitness account of Aboriginal cannibalism, falsely claiming that “we do not have a single eyewitness account of Aboriginal cannibalism.” When the Australian politician Pauline Hanson referred to the Aboriginal practice of cannibalism in 1997, an incensed Tatz equated it with “the blood libel against the Jews,” claiming “the Hanson vilification about cannibalism is not of the same magnitude or consequence, but it is very much in the same genre.”[C24]

The anthropological record totally undermines Tatz’s preferred narrative that the current epidemic of violence in Aboriginal communities is an historical aberration that can be attributed to their “genocide” and victimization at the hands of Whites. The above referenced Stephanie Jarrett notes that violence and abuse against women and children in Aboriginal communities are currently at “catastrophic levels” and that “It is important to acknowledge [the] link between today’s Aboriginal violence and violent, pre-contact tradition, because until policymakers are honest in their assessment of the causes, Aboriginal people can never be liberated from violence. … Deep cultural change is necessary, away from traditional norms and practices of violence.”[C25]Aboriginal woman Bess Price, in her forward to Jarrett’s book pointed out that “my own body is scarred by domestic violence” and noted that “Aboriginal people have to acknowledge the truth. We can’t blame all of our problems on the white man.”[C26]

Given the anthropological record, it is hardly surprising that today’s Aborigines are ten times more likely to commit homicide than Europeans and are ten to fifteen times more likely to commit a serious assault. The latest statistics from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare show that Aboriginal women are 32 times more likely than non-Aboriginal women to be hospitalized because of family violence. Similarly, Aboriginal men are 23 times more likely to be hospitalized. Two in five homicide victims (41 percent) were killed by a current or former partner, compared with one in five homicide victims. Aboriginal communities suffer Australia’s worst rates of family violence, which are causing Aboriginal women to be hospitalized at 35 times the rate of non-Aboriginal women. Aborigines are, consequently, vastly overrepresented in Australia’s prison population.

It is common to blame White Australia for this astounding level of incarceration. Richard Lynn cites an Australian sociologist who argues that “the key general cause of the perceived criminalisation of Aborigines is universally perceived to be socioeconomic deprivation and consequential exclusion” and that “the underlying issues of unemployment, poverty, ill-health, dispossession, and disenfranchisement are the causes of the over-involvement of Aborigines in prison” and that these are themselves “the product of indirect discrimination.” Lynn notes wryly that: “Thus it is the Europeans who are responsible for the high crime rates of the Aborigines.”[C27]

Part Four

The “Stolen Generations”

Colin Tatz has made the “Stolen Generations” the lynchpin of the “genocide” charge he levels against White Australia. The myth of the “Stolen Generations” was born in 1981 with the publication of a short pamphlet by a postgraduate history student, Peter Read, who argued that part-Aboriginal children were systematically removed to separate them from the rest of their race, claiming that “welfare officers, removing children solely because they were Aboriginal, intended and arranged that they should lose their Aboriginality, and that they should never return home.” He based this controversial thesis on interviews with Aborigines about their experiences with the welfare system, and his research into the New South Wales official records, from which he asserted that 5,625, or up to one in six Aboriginal children had been taken in New South Wales with the intent of permanent removal from their culture between 1883 and 1969.

Read, who wrote his pamphlet “at white heat in a single day,” initially wanted to call it “The Lost Generations” but his wife thought this too bland and suggested the more polemical “Stolen Generations.” Following its enthusiastic reception on the radical Left, Read, who later became Professor of History at the University of Sydney, hardened his thesis to claim Australian authorities sought not just to end Aboriginal culture, but to physically eliminate Aborigines altogether: “Their extinction, it seemed, would not occur naturally after all, but would have to be arranged.” In later writings, he drew an explicit analogy between the “Stolen Generations” and “the Holocaust.”[D1]

Read’s thesis was the default assumption for the polemical Bringing Them Homereport of 1997, the result of an inquiry by the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, which claimed that, in various parts of the country, up to one in five Aboriginal children were forcibly removed from their families during the sixty years prioe to 1970. This report relied on the anonymous and unverified testimony of people claiming to have been affected by removals. Echoing the later pamphlet by Read, a finding of genocide was presented: the removals were intended to “absorb,” “merge” and “assimilate” the children, “so that Aborigines as a distinct group would disappear.” It urged the federal government to apologize and offer compensation to the alleged victims and their families.

In 2008, then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd issued a formal apology, declaring “for the removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families, their communities, and their country. For the pain, suffering and hurt of these Stolen Generations, their descendants and for their families left behind, we say sorry.”

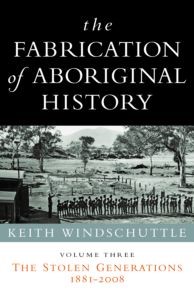

Two decades after the publication of Read’s pamphlet, historian Keith Windschuttle took the trouble to examine all 1,200 pages of records Read claimed to have studied, and found his research and conclusions, the two foundational props of the Stolen Generations myth, were filled with errors and distortions.[D2]

Tatz’s response to this devastating critique of Read’s figures and methodology is to label Windschuttle a “denier,” and insist “debates about quantification in genocide context are not a key issue. The fulcrum is intent, and the nature of the act(s) rather than raw numbers or percentages.”[D3] Thus, when the alleged actions that form the basis of the “Stolen Generations” charge are shown to bogus, Tatz resorts to arguing this is ultimately irrelevant because “intent” is sufficient for the charge to be levelled: “Did such actions occur? In any discussion of genocide, the intent rather than the motive and the actual outcome is all that matters.”[D4]

Tatz continues to cite Read’s pamphlet as a trusted source, and to assert that Aboriginal children were removed as part of a genocidal policy of assimilating them into the White Australian population. He also continues to recycle the totally discredited claim that 100,000 part-Aboriginal children were removed even though fellow “Stolen Generations” propagandist Robert Manne acknowledges the 100,000 number, contained in the Bringing Them Home report, is entirely spurious, the result of a journalist’s misunderstanding of an observation by Peter Read but then uncritically recycled during in the Bringing Them Home report, and repeated on many occasions since.[D5]

After carefully combing through the public records, Windschuttle put the total number of Aboriginal children taken into care from 1880 to 1970 in all states and territories of Australia at 8,250. This figure includes children fostered or adopted into White families, those forcibly or voluntarily separated from their parents for good (and sometimes bad) reasons, those sent with parents’ consent to be educated and trained elsewhere, and those taken away because they were neglected or abused by their parents.[D6] Windschuttle found no evidence of any policy by any state or federal government to steal children from parents to eliminate the Aboriginal race.

Despite Windschuttle’s debunking of the “Stolen Generations” myth, Tatz continues to assert that Aboriginal child removals, rather than motivated by concerns for child welfare, were prompted by White authorities responding to its “Aboriginal problem” by finding a “solution in biology” based on “the forcible removal of Aboriginal children from their parents, and their subsequent assimilation by intermarriage into white society.”[D7] To support this contention, he cites a handful of statements made by White Australian clergymen and bureaucrats at various points in the twentieth century, such as a brief statement from a national summit at Canberra in 1937 that: “The destiny of the natives of Aboriginal origin, but not of full blood, lies in their ultimate absorption by the people of the Commonwealth and it is therefore recommended that all efforts shall be directed to this end.”[D8]

Tatz takes for granted the desire expressed in this and similar statements (to assimilate mixed-descent Aborigines into the White Australian population) is “genocidal,” claiming that such ideas “go to the heart of genocidal thought and action, resorting to biological solutions to social and racial problems.”[D9] He also regards historical laws banning Aboriginal intermarriage with Europeans as a viciously racist “intrusion into marriage and sexual relations.”[D10]

White Australians are thus condemned for promoting the genetic assimilation of Aborigines and for preventing it.

Despite the statements Tatz cites as evidence to support his genocide charge, there is no evidence such views ever gained wide support or were translated into government policy. Historian Bain Attwood notes how “these statements of intent” are invariably “mistaken for action(s)” by the likes of Tatz and Manne who, in their writings, seem to assume the espousers of such views “won broad acceptance for their eugenicist policies and were able to implement them,” when the reality is that “a close reading of the historical record of actions does not support this claim.”[D11]

Despite their strident claims, Tatz and Manne have, as conservative journalist Andrew Bolt repeatedly points out, been unable to identify even ten children “stolen” just for being Aboriginal. The judiciary in the Northern Territory has been unable to find any evidence of a “stolen generation,” despite a huge test case and subsequent appeal. Activist lawyers picked Lorna Cubillo and Peter Gunner as their first and best two claimants from among 550 people in the Northern Territory who registered with them as having been “stolen” for being Aboriginal. The Howard government in power at the time fought the claims and won. The Federal Court in 2000 found that Gunner had been sent to Alice Springs by his mother for schooling, and Cubillo had been rescued from a bush camp where she was found abandoned by her father, her mother dead and her grandmother far away. Witnesses in the case who also signed up were all shown not to have been “stolen.”

After going through the records of Aboriginal policy in the Northern Territory, the judge ruled that the “evidence does not support a finding that there was any policy of removal of part-Aboriginal children such as that alleged by the applicants.” That finding was upheld on appeal and no evidence to the contrary has emerged since that finding. Court cases in Western Australia and South Australia have likewise found no proof children were “stolen” from their families just for being Aboriginal, rather than for being abandoned or abused. Those claiming to be “stolen” have, on closer checking, turned out to have been rescued instead—just as authorities still rescue Aboriginal children today.

Tatz claims in his book Australia’s Unthinkable Genocide that officials in Victoria in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries used their “powers to remove children of mixed descent, to absorb them physically and culturally and so end their Aboriginality” with between 20,000 and 35,000 children taken away “to institutions to extinguish their Aboriginality” and that this “became a cornerstone of action by state and federal administrators.”[D12] He neglects to mention that the Victorian Labor government was informed by its specially appointed Stolen Generations Taskforce in 2003 that while some 36 organizations were now helping the state’s “stolen generations,” not one truly “stolen” child could be found. In fact, the Aboriginal-led taskforce admitted that in the entire history of Victoria there had been “no formal policy for removing children.”

In Western Australia, a Supreme Court judge rejected claims there was ever any official program in the state to implement a “Stolen Generations” policy of forced assimilation into the White Australian community. Justice Pritchard dismissed damages claims by the Aborigines Don and Sylvia Collard and seven of their 14 children removed or made state wards. She specifically dealt with a claim that the children were removed “pursuant to a policy of assimilation of aboriginal children,”instead finding they were removed to safeguard their physical welfare, finding “the references to ‘assimilation’ in the evidence I have set out above are not sufficient to support a finding on the balance of probabilities that at the time of the wardships there was, within the Department of Native Welfare or the Child Welfare Department, the pursuit of a policy of assimilation of aboriginal people into white Australian society through the wardship of aboriginal children.”

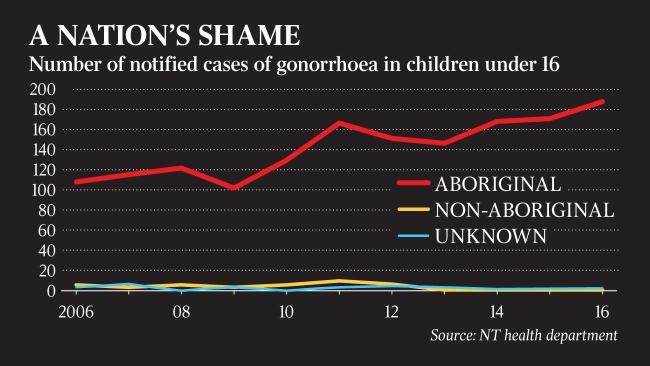

In truth, the so-called “Stolen Generations” saved thousands of children from systematic abuse, neglect and molestation. Figures released in 2016 by the Australian government Institute for Family Studies show that nearly 17,000 Aboriginal children are in out-of-home care, up 65 percent since former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s apology to the “Stolen Generations” in 2008. Reflecting on these figures, an incensed Greens MP recently declared: “It’s just ludicrous. Saying sorry (for the ‘Stolen Generations’), say you’re not going to do it again, and we still continue to see our children being ripped out of mothers’ arms.” The ABC interviewed a “stolen generations survivor” who likewise complained that this alleged child-stealing was still happening: “They have to stop taking our kids.” The ABC failed to explain that these children—like the “stolen generations” before them—were taken to save them from being neglected, starved, bashed or raped. Aboriginal children are today five times more likely to be hospitalized for assault and almost ten times more likely to be taken into care.

“Justification of genocidal practices”

Tatz labels any justification for the removal of Aboriginal children on welfare grounds as “lame attempts at justification of genocidal practices.” Nor, apparently, does it concern him that the “Stolen Generations” myth he so zealously propagates is killing Aboriginal children today by making authorities reluctant to save Aboriginal children from dangers that would once have prompted immediate intervention. The “Stolen Generations” myth necessitates denying that Aboriginal children are being removed today for good reasons as this implicitly concedes that the “Stolen Generations” were very likely removed for good reasons too. The results of this particularly noxious brand of anti-White activism are truly horrific for Aboriginal children today.