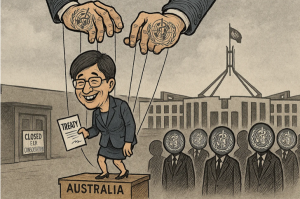

WHO’s Pandemic Agreement is adopted despite concerns about unelected institutions imposing global policies

6 min read

Members of the World Health Organisation (“WHO”) adopted a global pandemic accord on Tuesday, 20 May 2025; 124 countries voted in favour, no countries voted against, while 11 countries abstained and 46 countries were not present. The total votes cast don’t add up, but those are the numbers WHO has declared.

For the countries that abstained – of which, shamefully, the UK was not one – their concerns included loss of national sovereignty, lack of legal clarity and the risk of unelected institutions imposing policy.

Please note: The Pandemic Agreement has been called various names over the years. It has also been referred to as the Pandemic Treaty, Pandemic Accord and WHO Convention Agreement + (“WHO CA+”).

To ensure the Pandemic Agreement was adopted by the easiest possible route, WHO had determined that a vote need not take place, and instead it would be adopted by “consensus.”

Surprised that a “democratic institution” did not want to have a vote, Slovakia requested that a vote on the draft Pandemic Agreement take place, which Tedros the Terrorist attempted to stop hours before the vote was scheduled.

PHONE CALL WITH THE LEADERSHIP OF THE WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION

A few minutes ago, I received a phone call from the Director-General of the WHO, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, who asked me for the Government of the Slovak Republic to change its position and not request a vote on… pic.twitter.com/9cUO8C8mWC

— Robert Fico 🇸🇰 (@RobertFicoSVK) May 19, 2025

The vote was conducted by “a show of hands,” by “representatives” holding up their name plates, and then people counting the number of name plates raised. Which way countries voted was not recorded. It all sounds a bit dubious and fraught with error, with no way of checking whether an error, inadvertently or deliberately, has been made. A “show of hands” might be a good way to gauge how many bags of sweets to buy for a school outing, it certainly isn’t the way to vote on a global agreement.

To watch a video of the vote, go to WHO’s 78th World Health Assembly webpage, HERE, and select the ‘Committee A’ tab shown under the current video. Then from the list of ‘Committee A’ videos, select ‘WHA78 – Committee A, Second Committee A Meeting, 19/05/2025 – 18:50-21:40’. The “show of hands” voting begins at timestamp 02:47:20. The results were (see timestamp 03:08:08):

- Number of members entitled to vote, 181

- Number of members absent, 46

- Number of abstentions, 11

- Number of members present and voting, 124

- Number of votes in favour, 124

- Number of votes against, 0

- Number of votes required for the majority of two-thirds of members present and voting, 83

Yes, the Chair read out that the number of members present and voting was the same as the number of votes in favour; 124. In other words, the Chair claimed that all countries that had representatives present at the meeting voted in favour of the Pandemic Agreement. When no name plates were raised during the time allotted for votes against the Agreement, the so-called country representatives gave themselves a standing ovation.

However, the total number of countries present and voting according to the Chair does not add up. Countries that abstained were present, such as Slovakia, which means that the Chair made a “mistake” in claiming that 124 members were present and voting or made a “mistake” in saying that 124 voted in favour of the Pandemic Agreement. Either there were 135 members present and voting (in which case two-thirds majority was 90, not 83 as claimed) or not all the 124 countries present voted in favour of the Agreement (11 abstained). As the votes were not recorded and the only evidence that exists is a video showing a partial picture of the room, what the Chair said and what the vote counters claimed can’t be checked. How convenient for anyone who wishes to manipulate the results of a vote.

Putting aside the dubious voting methods, the absence of the United States, which has begun the process of withdrawing from the WHO, casts doubt on the Pandemic Agreement’s effectiveness, according to Reuters. Nonetheless, its advocates were hailing it as “a good starting point” and a “foundation to build on.”

As we mentioned in an article on Friday, the Pandemic Agreement will not go into effect until an annexe on the sharing of pathogenic information is agreed.

Dr. Meryl Nass was asked what the adoption of the Agreement means; she responded by referring to four previous articles she had published, read HERE.

In a Twitter (now X) thread posted yesterday, independent journalist Lewis Brackpool summarised what has happened and where it is heading. We have reproduced Brackpool’s thread below.

The WHO Pandemic Agreement Has Now Passed

A Twitter thread by Lewis Brackpool

The WHO Pandemic Agreement has now been passed. There was no parliamentary vote, no public debate, and no referendum.

This thread explains what was agreed, how it happened, and why concerns about sovereignty, accountability, and global governance are growing.

On 20 May 2025, WHO member states adopted the organisation’s first international Pandemic Agreement at the 78th World Health Assembly in Geneva.

The treaty was adopted by consensus, not a formal vote, which means that governments, including the UK, signalled approval without domestic scrutiny.

The treaty is designed to address failings exposed by how countries “handled covid-19.”

It outlines legal commitments to:

- Share pathogen samples and genetic data.

- Distribute vaccines and therapeutics “equitably.”

- Strengthen international surveillance.

- Comply with WHO-led emergency declarations.

- Develop global digital health certification systems.

This agreement is not limited to pandemic response. It’s based on the WHO’s “One Health” framework, which views human, animal and environmental health as interconnected.

Critics (rightly) argue this broadens the WHO’s scope, allowing it to influence food systems, climate policy, agriculture and land use under the guise of “pandemic prevention.”

While the WHO cannot override national law, the treaty creates binding international obligations. Governments may use it to justify emergency laws or sweeping public health powers, while shielding decisions behind the language of “international compliance” or “global coordination.”

The WHO is not a democratic institution. Its Director-General, Tedros Ghebreyesus, is not elected by citizens, but appointed via a process dominated by diplomatic negotiations between member states.

His past controversies, including handling of the early covid outbreak and ties to China, have fuelled concerns about impartiality.

The WHO’s top funders are not primarily governments. As of 2023, its largest contributors included:

- Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

- GAVI Alliance

- UNICEF

- The European Commission

- Germany and the US

Private foundations now shape global public health priorities – without any electoral mandate.

Among the more contentious provisions of the treaty are proposals to implement a Pathogen Access and Benefit-Sharing (“PABS”) system. This would allow WHO to access pathogen samples from any country and redistribute pharmaceutical products under “equitable” frameworks – potentially overriding domestic vaccine supply chains.

The treaty also encourages states to adopt digital health documentation systems, which could evolve into permanent digital IDs tied to vaccination or health status. While presented as public health tools, such systems have been heavily criticised by civil liberties groups as intrusive, coercive and open to mission creep.

Several countries abstained or objected during the drafting phase. These include:

- Poland

- Russia

- Italy

- Iran

- Slovakia

Their stated concerns include loss of national sovereignty, lack of legal clarity and the risk of unelected institutions imposing policy.

In the UK, there has been virtually no parliamentary debate over the treaty. No formal statement has been made by the Prime Minister or the Health Secretary. Despite the agreement’s long-term implications, the UK has participated in negotiations quietly, bypassing public scrutiny.

The adoption of this treaty reflects a broader trend: The shift from nation-state governance to transnational managerialism. Under this model, decisions affecting millions are increasingly shaped by technocrats, NGOs, foundations, and UN agencies – none of whom are directly accountable to voters. James Burnham’s ‘The Managerial Revolution’ explains this, read HERE.

This is not a conspiracy theory. It is a structural change in how global policy is made – particularly in moments of crisis.

What covid began, the WHO treaty formalises: Emergency governance, centralised authority and the use of global health as a gateway to broader control.

If democratic governments can enter binding international agreements on pandemic policy without consulting their citizens, then who governs in a crisis? The answer, increasingly, is: Those you cannot remove from office.

The WHO Pandemic Agreement is a landmark. Not just in public health, but in global governance. It centralises authority, weakens national sovereignty and embeds unelected influence at the heart of crisis response.

The public was never asked.

About the Author

Lewis Brackpool is an independent journalist and social commentator from the southeast of England. He hosts “The State Of It,” a podcast where he discusses politics, culture, and agendas. Brackpool also writes for Substack under the publication ‘The State of It’, where he explores topics such as politics, culture and modernity.

Source: https://expose-news.com/2025/05/21/whos-pandemic-agreement-is-adopted/