Assimilate & Destroy: The Rockefeller Foundation’s Role in Exploiting Then Suppressing Natural Medicine

BY DR TIM COLES

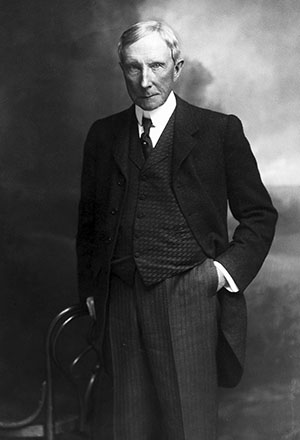

Born in New York, John Davison Rockefeller (1839-1937) was the world’s first billionaire1 (he’d be worth around $13.7 billion in today’s money). As a Republican, Rockefeller supported Abolition, back when southern Democrat-voting industrialists profited from their human property. He was also a Methodist/Baptist Christian who believed that god had made him rich.

In 1864, he founded the grain and produce company, Clark, Rockefeller, & Co., with business partner, Maurice Clark (1827-1901). The company profited from the American Civil War (1861-65)2 and Rockefeller used his money to establish the company that made him his fortune: Standard Oil of California. With notions of the Protestant work ethic and Christian charity, Rockefeller and his employees attempted to craft an image of the family dynasty as philanthropic.

THE FOUNDATION AT HOME: “HEALTH IS PROFITABLE”

ROCKEFELLER ABROAD: “HEALTH HAS ADVANTAGES OVER MACHINE GUNS”

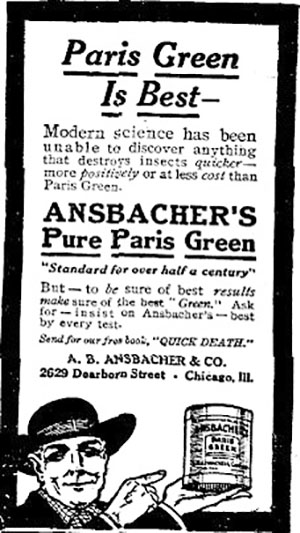

“Paris Green” was named after its use against rats in the sewers of the famous French capital. It is an arsenic-based toxin that was used as an insecticide. It was mass-produced in New York. The Bulletin of the Industrial Commission reported at the time that “[c]onsiderable illness has been found to exist among many of the workers engaged in this production.” The Department of Labor described it as “a dangerous poison and sickness results from the breathing of air containing it, through broken skin, and through the mouth.”28 The Rockefeller International Health Board experimented in anti-malaria techniques in Brazil, Bulgaria, El Salvador, India, Italy, the Netherlands, Nicaragua, Palestine, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico. The League of Nations argued that sanitation was key to beating disease, but Rockefeller lobbyist and physician Lewis Hackett (1884-1962) argued for the use of “Paris Green.” The International Health Board used its propaganda to promote the results of a dubious, preliminary study in Italy.

One historian writes: “the anti-mosquito strategy… laid the groundwork for the subsequent DDT revolution in malariology.”29 DDT is also a toxin trialled by the US Typhus Commission. During the Second World War (1939-45), the Rockefeller Foundation’s health institutes tested DDT on German and Italian prisoners of war, as well as on Algerian inmates before heralding DDT operations a success in Sardinia.30

Rockefeller’s motives for eradicating mosquitos are exemplified by the case of Mexico. Disease historians note that the yellow fever virus mainly affected the nation’s shipping ports that were crucial for US corporate profits, including Rockefeller’s Standard Oil. The company relied on the malaria-ridden port of Veracruz.31 In addition to using poison to blitz mosquitos to clear ports for profit, the Foundation used its eugenics ideas to encourage Mexican women to produce “strong” babies that could grow into healthy workers.32

COMING AROUND

After WWII, the Foundation lost its direction. The so-called third world became a battleground between US imperialism and Soviet dominance, with the Rockefeller Foundation struggling to design an internationalist, post-War policy. The giant, US, post-War machine referred to by future President Dwight D. Eisenhower as the “military-industrial complex” meant that research grants were awarded through the government’s National Science Foundation, making Rockefeller money less immediately appealing to young researchers. The Rockefeller Foundation initially succeeded by funding the shift in research from chemistry to biology, particularly the study of proteins for vaccination. “That decision has been widely viewed as stimulating the rise of the new field of molecular biology.” What began as schools for research turned into captive instruments that awarded funding for clear proposals, not for theoretical research. But theoretical research is where major breakthroughs tend to occur.33

The founding of the World Health Organization in 1948 coincided with the dissolution of the Rockefeller Foundation’s International Health Board, which was subsumed into the Division of Medicine and Public Health in 1951.34 The Rockefeller Foundation failed to make the shift from protein to DNA research and lost ground to big biotech firms, like Monsanto (now Bayer). But cultural changes began to take shape.

The Foundation started out taking natural plants from traditional medicine practitioners and using them to promote synthetic pharmaceuticals. But, having been part of the mechanisms that destroy the world with their interests in oil, banking, and pesticides, the Rockefellers have now seen profit-potential in solutions to the problems they allegedly helped to create. In more recent years, the Foundation and Rockefeller’s successors have come to recognise the value of naturopathy.

A few years ago, scientists contrived a new epoch: the Anthropocene. In the Anthropocene, the dominant species causing potentially irreversible destruction to the planet’s ecosystem is the human. The Rockefeller Foundation and The Lancet published a report stating: “Far-reaching changes to the structure and function of the Earth’s natural systems represent a growing threat to human health.”

Having gone from seeing the human body as a factory comprised of separate parts in the 19th century and promoting molecular biology to stimulate biotech profits in the 20th, the Foundation now decries “an increasingly molecular approach to medicine, which ignores social and environmental context.”35

Sometimes, the parasitic greed of the ruling classes destroys the host, in this case the planet, forcing our “betters” to modify their propaganda in the new ages they contrive.

Footnotes

1. Natalie Burclaff, “Rockefeller: Making of a Billionaire,” Inside Adams Science, Technology and Business, Library of Congress, 14 January 2020, blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2020/01/rockefeller-billionaire

2. Ron Chernow (1998) Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, London: Random House, 25-31

3. Berrien C. Eaton (1949) “Charitable Foundations, Tax Avoidance and Business Expediency,” Virginia Law Review, 35(7): 809-61

4. Bill Clinton, “Introduction” in Eric John Abrahamson (2013) Beyond Charity: A Century of Philanthropic Innovation, New York: Rockefeller Foundation, 23

5. American Medical Association, “AMA history,” no date, www.ama-assn.org/about/ama-history/ama-history

6. Robert B. Baker (2014) “The American Medical Association and Race,” American Medical As-sociation Journal of Ethics, 16(6): 479-88

7. J.T.H.J. Dekkers (2009) What about Homeopathy? A comparative investigation into the causes of current popularity of homeopathy in The USA, The UK, India and The Netherlands, Master’s thesis, University of Utrecht, 20-24, dspace.library.uu.nl/bitstream/handle/1874/35695/ScriptieJorisDekkers.pdf

8. Robert G. Slawson (2012) “Medical Training in the United States Prior to the Civil War,” Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 17(1): 11-27

9. J. Andrew Mendelsohn (2002) “‘Like All That Lives’: Biology, Medicine and Bacteria in the Age of Pasteur and Koch,” History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences, 24(1): 3-36

10. Quoted in E. Richard Brown (1980) Rockefeller Medicine Men: Medicine and Capitalism in America, Berkeley: University of California, 115-16

11. Quoted in Brown, op. cit., 120

12. Quoted in Brown, op. cit., 113

13. Brown, op. cit., 105

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), “Hookworm FAQs,” no date, www.cdc.gov/parasites/hookworm/gen_info/faqs.html

15. Angela Matysiak (2014) Health and Well-Being: Science, Medical Education, and Public Health, New York: Rockefeller Foundation, 59-75

16. A.E. Birn (2014) “Backstage: the relationship between the Rockefeller Foundation and the World Health Organization, Part I: 1940s-1960s,” Public Health, 128: 129-40

17. Ilana Löwy and Patrick Zylberman (2000) “Medicine as a Social Instrument: Rockefeller Foundation, 1913–45,” Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, 31(3): 365-79

18. Quoted in Brown, op. cit., 124

19. Quoted in Brown, op. cit., 124

20. M.R. Lee (2011) “The history of Ephedra (ma-huang),” Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, 41: 78-84

21. Editorial (2014) “China Medical Board: a century of Rockefeller health philanthropy,” The Lancet, 384: 717-19

22. United Nations News, “WHO chief warns against COVID-19 ‘vaccine nationalism’, urges support for fair access,” 18 August 2020, news.un.org/en/story/2020/08/1070422

23. One of many: Denise Chow, “‘Reckless and foolish’: Why Russia’s vaccine has experts alarmed,” NBC News, 11 August 2020, www.nbcnews.com/science/science-news/reckless-foolish-why-russia-s-vaccine-has-experts-alarmed-n1236466

24. Ian Jones and Polly Roy (2021) “Sputnik V COVID-19 vaccine candidate appears safe and effective,” The Lancet, 2 February 2021, doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00191-4

25. Maria Deloria Knoll and Chizoba Wonodi (2020) “Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine efficacy,” The Lancet, 397(10269): 72-74

26. World Health Organization, “Yellow fever,” 7 May 2019, www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/yellow-fever

27. Löwy and Zylberman, op. cit.

28. Monthly Review of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Dangers in the Manufacture of Paris Green and Scheele’s Green,” 5(2): 78-83

29. Darwin H. Stapleton (2004) “Lessons of History? Anti-Malaria Strategies of the International Health Board and the Rockefeller Foundation from the 1920s to the Era of DDT,” Public Health Reports, 119(2): 206-15

30. Ibid.

31. Andrew L. Knaut (1997) “Yellow Fever and the Late Colonial Public Health Response in the Port of Veracruz,” Hispanic American Historical Review, 77(4): 619-44

32. Linnete Manrique (2016) “Dreaming of a cosmic race: José Vasconcelos and the politics of race in Mexico, 1920s–1930s,” Cogent Arts & Humanities, 3(1218316): 1-2, 11n5

33. P. G. Abir-Am (2010) “The Rockefeller Foundation and the Post-WW2 Transnational Ecology of Science Policy: from Solitary Splendor in the Inter-war Era to a ‘Me Too’ Agenda in the 1950s,” Cenataurus, 52: 323-37

34. Rockefeller Foundation, “International Health Division,” Archive, rockfound.rockarch.org/international-health-division

35. Sarah Whitmee et al. (2015) “Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health,” The Lancet, 386: 1973-2028

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.